Ms Wong (the applicant) and her family applied for Temporary Business Entry (Class UC) (Subclass 457) (457) visas on 2 March 2018. At the time of application, the applicant did not hold a substantive visa.

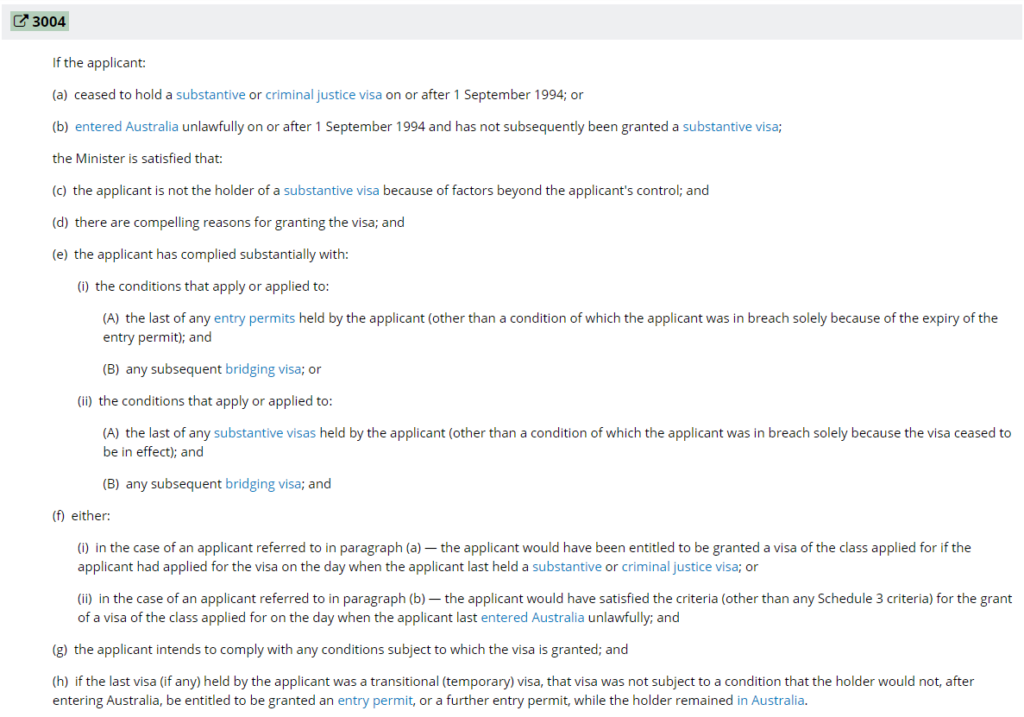

Among other things, the primary criteria required that if the applicant were in Australia at the time of application and did not hold a substantive visa, they would need to satisfy Schedule 3 criteria 3003, 3004, and 3005.

On 8 August 2018, a delegate of the Minister of Home Affairs (delegate) decided not to grant the visas on the basis that the primary applicant did not meet Schedule 3 criterion 3004(c). This criterion requires that if the applicant does not hold a substantive visa, the Minister should be satisfied that this is because of factors beyond the applicant’s control.

On 18 February 2021, the applicant appeared before the Tribunal to give evidence and present her arguments. The Tribunal accepted her claims and subsequently remitted the matter on 19 February 2021, with the primary finding that an agent’s negligent actions can constitute “factors beyond control”.

What is the relevant law?

Clause 457.211 operated to requires that an applicant who is in Australia at the time of application holds a substantive visa other than a Subclass 771 (Transit) visa or a special purpose visa.

If the applicant does not hold a substantive visa at the time (which the applicant in this case did not), they may still satisfy this clause so long as:

- the last substantive visa they held was not a Transit or special purpose visa; and

- they satisfy Schedule 3 criteria 3003, 3004 and 3005.

The Tribunal was satisfied that the applicant satisfied criteria 3003 and 3005, with 3004 being the primary criterion in question.

If enlivened, criterion 3004 requires that the Minister be satisfied that:

Analysis

3004(c): Factors beyond control

The applicant ceased being the holder of a substantive visa because of a previous 457 visa application which was submitted on 14 November 2016. At the time, the applicant’s then-migration agent ticked the box indicating that if the application for nomination was refused, the visa application is to be withdrawn.

As a consequence of the withdrawal box being ticked by her agent, when her employer’s nomination application was refused, the applicant’s visa application was taken to have been withdrawn and the applicant ceased to be a substantive visa holder.

The applicant claimed that she did not have to opportunity to review her visa application, and would not have agreed to ticking the box for automatic withdrawal of her visa application because it would remove any of her rights for review. The applicant considered this misconduct on her migration agent’s behalf, submitting that her migration agent submitting the form without her consent amounted to a factor beyond her control.

It was submitted that as a later nomination was lodged and approved by her employer, it is highly likely that had the agent not engaged in that misconduct, she would not have found herself in this position of lodging a further subclass 457 visa application as a bridging visa holder. It was further submitted the applicant would likely have been able to pursue her subclass 457 visa application that had been lodged while she was holding a substantive visa with a further nomination application.

Policy set out in schedule 3 provides that migration agent inaction would not ordinarily satisfy this criterion, because the actions of a migration agent are taken to be the actions of the applicant. However, it also says “these types of cases need to be considered on their facts. If a migration agent has been deregistered, it may be reasonable to find that negligent action by the agent that has affected the applicant was a circumstance beyond the applicant’s control.” In this case, the issue was not inaction, but action without consent. Therefore, this was not ordinary action by the agent on behalf of the applicant, but negligence.

The Tribunal therefore accepted the applicant’s argument that the actions of her migration agent amounted to a factor beyond her control.

3004(d): Compelling reasons

The Tribunal accepted that cumulatively, the applicant’s submissions as to why she should be granted the visa were compelling. These reasons included (among other things) that she had not seen her young children for two years, she had formed close ties in Australia, she had studied and gained post-graduate work experience in Australia and was working in a remote area of Western Australia which was suffering from a skills shortage.

3004(e): Substantial compliance

The Tribunal accepted that there was no evidence to suggest that the applicant was not compliant with all conditions of her previous substantive visas and bridging visas. This includes the fact that the applicant always maintained adequate health insurance in Australia.

3004(f): Would have satisfied the criteria

The Tribunal accepted that the applicant would have satisfied the criteria to be granted the visa on the day she held her last substantive visa. On 16 November 2016, the last day the applicant held her last substantive visa, she had a willing sponsoring employer and had the requisite skills and qualifications for the job opening. [

The final decision and what this means for similar matters

The Tribunal remitted the application for reconsideration, with the direction that the applicant meets criteria 3003, 3004 and 3005 of schedule 3. In particular, the following is relevant:

- migration agent action without consent of the applicant can be considered beyond the applicant’s control; and

- compelling reasons for granting of a visa can be considered cumulatively.

Both of these factors are beneficial for an applicant seeking to satisfy 3004 of Schedule 3.

View the full decision here.

How can Hannan Tew help?

Hannan Tew Lawyers have assisted a significant number of individuals meet complex Schedule 3 criteria for a wide variety of visa subclasses. If you are in a similar situation, feel free to contact us by email at [email protected] or phone +61 3 9016 0484.